Veneer - A Mystery to many woodworkers

Most

amateur woodworkers and many professional woodworkers have never used

wood veneer in a project. But most of us have used plywood

products in our projects. And we all know that plywood is made

from veneer, usually oak, cherry, maple, and to a lesser extent, more

exotic woods like walnut. Plywood is also available in some

tropical hardwoods, but finding it is exceedingly difficult. For

my Mahogany entertainment center, for example, I need plywood made with

very fine South American Mahogany veneer. I seriously doubt such

plywood even exists in a commercial product, but if it did, I would

expect it to be extremely expensive. So I really only have two

options: I could make the entire project out of solid

Mahogany. The problem doing this is very simple, Mahogany

hardwood is very scarce and in my area, is priced starting at over

$11.00 per board foot. And I would have to find enough solid

mahogany that is consistent in color, figure, and free from defects,

and in the thickness I need for each of the constituent parts.

This would be a very expensive option and difficult option.

My other option is to make my own plywood out of high quality Mahogany

veneer, which means I only need to find a relatively small amount of

solid Mahogany for the legs, door styles and rails, etc. The

very first class I ever took at the

Marc Adams School of Woodworking was a class taught by

Darryl Kiel, president of

Vacuum Pressing Systems,

on the basics of working with veneer. This class completely

changed my woodworking life and taught me a wonderful and very

different approach to woodworking. Even extremely scarce and

exotic hardwood that would be impossible to find as solid wood is

usually available as veneer. In fact, by turning precious and

scarce hardwood into veneer, veneer manufacturers are effectively

preserving a scarce resource. By learning to work with veneer, a

woodworker is able to take advantage of this fact in his own projects.

Finding veneer locally, however, might be a challenge in itself.

Small quantities of some veneers are available through woodworker

stores like Woodcraft, but you will not find large quantities or scarce

veneer. For that, I use

Certainly Wood out

of New York. They have a huge selection of veneers from all over

the world, and have an extremely knowledgeable sales staff. There

are numerous other sources on the Internet for veneer, but I have been

very pleased with both the quality of the veneer I received from

Certainly Wood and with their sales staff.

If you do any serious work with veneer, a must have tool is a vacuum press. The

vacuum press works on the principle that if you remove all the air from

inside the bag, the weight of the atmosphere will press evenly on

whatever is inside the bag. Depending upon your elevation above

sea level, a vacuum press is capable of putting between 1500 and 1700

pounds per square foot of pressure on the object you are gluing.

On the right is a picture of some panels being pressed between two MDF

platens.

Substrate and Glue

Iíve heard a lot of misinformation about gluing veneer, particularly

regarding the type of glue you should be using. The absolute

worst glue you can use on a veneer project is contact cement. Iím

amazed at how often I see some magazine advise using contact cement for

veneer, or worse yet, occasionally on a woodworking television

show.

Contact cement is formulated to be used with rigid material like formica. Contact cement

does not form a rigid glue line and

always maintains a certain amount of flex or give.

White and yellow glues are better, but still do not result in a rigid

glue line. Additionally, the working time for white or yellow

glues is relatively short so you have to work quickly before the glue

sets up. The best glue for working with veneer is one of a family

of glues based on urea formaldehyde because it has a relatively long

open time and cures based on a catalytic reaction.

Iíve

used a product called Unibond800 for years and have great success with

it. Unibond800 has the unique characteristic of an absolutely

rigid glue line after curing. This makes this glue ideal not only

for veneer but also for bentwood lamination work. When using it

for bentwood lamination, I experience virtually no spring back after

removing the work piece from the glue form.

It does have a couple of drawbacks. First, it has a relatively

short shelf life of about 6 months to a year, depending upon the

temperature youíre storing it at. And second, since you add a

catalyst powder to the glue, you must use whatever you mix because

whatever is left will cure rock hard. Third, and this is a

relatively minor one, the glue cures best in a warmer

environment. If you are doing a glue up and the temperature is

below 70 degrees, you need to cover the project with a heating blanket,

or else the glue might not set at all.

The substrate you choose needs to be perfectly flat, free from any voids or surface defects, and as free from

seasonal woodmovement as possible. Plywood is an excellent

choice, but you need to select high quality plywood that is free from

internal voids. MDF is a wonderful substrate for veneer because

it is dead flat, free from any internal voids, and will not change

dimensions seasonally. The pictures on the left and right show a piece

of MDF that Iíve applied 3/8 thick mahogany edge banding to. I"m

using a hand plane to bring the edge banding exactly to the surface of

the MDF, and will eventually glue the veneer on top of the edge

banding, giving the illusion of solid wood. There are really only

two techniques for edging a veneered panel:

- Veneer the panel, trim it, then apply the hardwood edge.

This technique must be used for off-the-shelf plywood, but not

necessarily for shop-pressed panels. An advantage to this

technique is that the hardwood edge will effectively capture and

protect the delicate veneer. The disadvantage is that you must

figure out some way to level the appled hardwood edge perfectly with

the veneer.

- Apply the hardwood edge to the naked panel. Finish and

level the hardwood perfectly flush with the surface of the

substrate. By making the edging slightly oversized knowing it

will be trimmed to final size after application of the veneer, you now

veneer over both the MDF and the hardwood edge. After the glue is

set, the edges can be trimmed using a panel saw or table saw, the edge

treatment can be done to achieve a finished look. The main

advantage to this technique is that it becomes almost impossible to

distinguish where the veneer ends and the hardwood edge begins.

The disadvantage is that the width of the applied hardwood edge must be

limited to a relatively small size - 3/8 to 1/4". Leaving the

hardwood edge any wider runs the risk that natural wood movement in the

hardwood edge will result in cracks in the veneer. With a

relatively narrow hardwood edge, edge treatments are quite limited to a

gentle roundover.

Specialized Tools for Veneer

|

|

Cutting veneer can

be done using a variety of tools depending upon the type of veneer and

the specific type of cut being made. A good straightedge and a

veneer saw is one of the more common methods.

|

The fabric cutter

(white with orange) is an example of a tool designed for another

purpose (cutting fabric) that can be extremely useful for certain types

of veneer cuts. In addition to the veneer saw and fabric saw, I

occasionally us a very, very sharp chisel that Iíve slightly modified

to cut veneer, and I also have a surgeonís scalpel that is ďscaryĒ

sharp. I tend to use the scalpel more when Iím doing marquetry or

when Iím trying to cut difficult veneer with squirely

grain. The soft bristle brass brush is used to massage the

moist veneer tape to get the best possible surface contact with the

veneer tape. The little roller is a wallpaper roller I stole from

my wife years ago. I use it to massage the seams to get the seam

perfectly flat.

|

Veneer

tape is probably the most unusual item. It is a thin paper tape

with a moisture activated glue on one side. This tape dispenser

makes moistening and cutting the tape easy. Veneer tape comes in

various widths and can easily be applied without a dispenser. A

simple moist sponge is really all you need to get started.

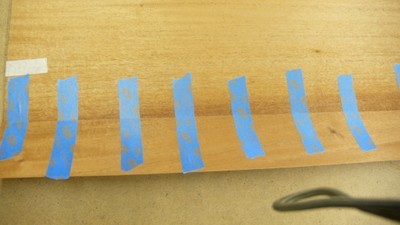

The following sequence of photos shows the process of seaming two

pieces of veneer together. I first cut both pieces for the joint

using a straightedge and veneer saw. Next I use blue painters

tape to carefully align the two edges together. I use one inch

veneer tape across the joint followed by two inch veneer tape along the

joint. The bottom photo shows the result after pressing.

The photo will not really show it, but the resulting joint is virtually

invisible!

|

Here are two pieces of veneer that have been edge jointed and are ready to be joined together.

|

|

The first step is to carefully bring the edges together using

blue tape. The technique is to start at one end and work toward

the other end using one strip of blue tape at a time. The idea is

to "stretch" the blue tape across the seam causing the tape to pull the

seam tightly together. This is harder to explain than it is to

do! The basic idea is to press the tape to the veneer on one side

of the joint, then stretch the tape across the joint (gently) before

you adhere it to the other side.

|

|

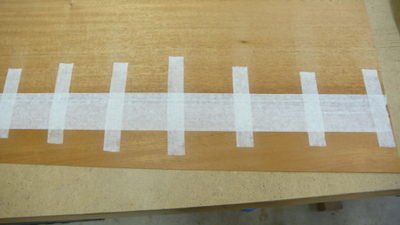

Moisened veneer tape is next placed across the joint.

There is no need to "stretch" the veneer tape because it will have a

natural tendence to shrink as it dries, thus pulling the joint tightly

together.

|

|

After a few minutes, it is now safe to remove the blue tape.

|

|

I use a wide piece of veneer tape to go lengthwise across the

seam. The wide piece of tape is applied directly over the narrow

pieces.

|

|

After pressing, the joint virtually disappears!

|