mission finish for quarter-sawn white oak

On this Arts and Crafts glider rocker, the finish is every bit as

important as the construction and joinery. Arts and Craft

furniture is often made from highly figured quarter-sawn white oak that

is finished in such a way as to emphasize the medulary ray fleck

pattern. Traditionally this classic finish was achieved by fuming

the piece in a strong ammonia vapor. The ammonia vapor reacts

with the natural tannic acid in the white oak leaving a lovely brown

appearance. The ammonia used for this process must be very

concentrated, much more so than the ammonia commonly available in

stores. You have to construct a sealed tent, place the piece to

be fumed inside with a dish of ammonia, then seal the tent and wait

until the ammonia reacts with the tannic acid and the look you are

after is achieved.

I chose a much different approach for this project, deciding to rely

instead on the finishing skills I learned during a week-long finishing

class I took a couple of years ago at the Mark Adams School of

Woodworking.

Story board

The single most important thing I learned about finishing is to begin

each woodworking project already having worked out the finishing

schedule. Before making the first cut on the project, create

several “story boards” with different finishes and choose the one you

will use for the project. Since I was making five glider rockers,

one for myself and four for good friends, I wanted to discuss the

finishing options well in advance and give my friends the chance to

select the look they wanted for their own chair. For many

finishes, this is as simple as picking up several different stains and

top coats at the local home center, and using each on a small sample

board to create an example of how the wood looks using each particular

combination. But you can’t achieve the look I was after out of a

can from the home center.

The look I wanted required the use of several products applied one

after the other, and most interestingly, the final look does not appear

until the final top coat is applied. I created several

storyboards, each of which illustrates the metamorphosis the wood goes

through as you work your way through the finishing schedule. By

using masking tape to cover over a small portion of the board after

each step, the impact of that step is revealed. This is important

if for no other reason than to help you keep your sanity as you work

through the various steps. As you apply each step in the

finishing schedule, the result leave the piece looking terrible.

You need the story board to refer back to so you can prove to yourself

you are on track. Without a story board, the finishing process

will be a miserable experience fraught with the nagging feeling that

you’ve just ruined months of work.

Another benefit to creating story boards is to learn how difficult each

step will be, and if it would be better to finish some or all of the

piece prior to final assembly. For this glider rocker, the lower

rocker assembly is a complex group of parts that hang the chair from

bearings that are tightly press fitted into holes drilled in the

various parts. After all these parts are assembled and the

bracing applied to make the lower assembly rigid, it simply would have

been impossible to access the parts for finishing. So I decided

to finish the lower assembly for each chair separately, but felt I

could do the upper part of the rocker – the chair itself, fully

assembled. Even this, however, was a dicey decision that balanced

the difficulty of applying the finish to the interior parts of the

chair against the added complexity of finishing them before assembly

then having to glue and clamp the parts together.

Creating a story board also helps you solve a problem with many

variables that include the species of wood and how it is cut from the

log, and from what part of the log it is cut. Even wood cut from

the same log can look quite different if it is a plain sawn board, a

rift cut board, or a quarter sawn board. Sap wood and heart wood

can behave very differently under an applied finish and if you are

working with wood with a lot of sap wood, you might have to find a way

to treat the sap wood differently to cause it to blend harmoniously

into the rest of the board. The specific type of colorant you

choose can have a tremendous impact on the final look. Dye stain

colors the wood without using pigments which tends to accentuate the

figure but not the grain. Pigment stains accentuate grain but

tend to hide figure. Some top coats are crystal clear and others

have an amber cast. Top coats themselves fall into families like

shellac, lacquer, and varnish. Lacquer and varnish can be

solvent-based or water-based. The number of variables can become

very large and when you think about it, it really makes absolutely no

sense to build a project and wait until the very end to think about how

you are going to finish it. Doing a storyboard at the beginning

of the project, determining exactly how you will achieve the look

you’re after, is inherently logical. This simple lesson has made

an unbelievable difference in my woodworking.

Finishing Environment

Good lighting is a critical factor when finishing a woodworking

project. I've collected several quartz halogen high intensity

lamps over the years that work very well for this application. My

shop is well lit with flourescent lighting but the extra light provided

by these lights really helps. I made a finishing table from

plywood that allows me to easily rotate the piece I'm working on.

This is a godsend for someone like me with bad knees because it allows

me to sit in one place and rotate the piece as needed. The

finishing table is simply two round 3/4" plywood disks that are

connected together using cast iron pipes. I purchased two 24"

long cast iron pipes, one 1 1/2 in and the other 2". The 1 1/2 in

pipe fits almost perfectly inside the 2" pipe, and by using the proper

pipe flange screwed to the top and bottom piece of plywood, the top

freely rotates. This system is very flexible by simply using

longer pipes to make the table higher or shorter pipes if the piece I'm

working on, like this chair, is taller.

Finishing Process

Step 1: Raise the grain in preparation for applying the finish.

This step is only necessary because I decided to use an alchohol and

water mixture for the dye stain I would be applying. If I was

using an alchohol dye, or an oil based stain, this step is not

needed. Using distilled water, I whetted the entire chair and

allowed it to dry. I used 320 grit sandpaper and very, very

lightly went over the entire surface. The idea is to gently knock

off the tiny nibs of wood raised by the application of the water.

Once you do this, you can apply water again and the grain will not be

raised.

Step 2: Apply the dye stain.

I

used a 50/50 mixture of distilled water and denatured alchohol, adding

enough transtint dye to create the proper tint. I worked out the

exact proportions when I made my story board and simply scaled the

proportions up to make a quart of dye. It took about ½ quart of

dye per chair. I applied the dye using a disposable spray

bottle. By spraying the dye over a small area, then using a rag

to evenly distrubute the dye, I gradually worked my way through

covering the entire chair. Note that I used a resperator while

spraying the dye because the vapor and mist created with this process

tends to hang in the air.

Step 3: Seal with Shellac

I

intended to apply an oil-based glaze over the dye, so it was critical

to seal the entire piece with a 1 pound cut coat of shellac.

There are many ways to apply shellac, and with only a 1 pound cut, it

is very easy to apply the shellac with a rag. The idea is to get

an even coat of shellac on the entire piece to create a separation

barrier between the dye and the subsequent coats. The great thing

about shellac is that it is almost universally compatible and can be

used as a sealer between incompatible finishes.

Step 4: Apply the glaze

A

glaze is a colorant you apply over a sealed surface that drys very

slowly, works it way into the wood pours, but not into the more dense

surfaces of the wood. For the quartersawn white oak, the medulary

ray flecs are very dense compared to the rest of the wood, which is

usually described as being open pored. I wanted the glaze to

darken the open pours but not color the ray flecs. This effect is

simple to achieve because the glaze will find its way deep into the

open pores of the wood but can easily be wiped off the the ray

flecs. When applying a glaze of this type, you apply it very

liberally with a stiff brush, working it deep into the pores, then use

a rag to wipe off the excess glaze. An oil based glaze like the

one I used has a very long drying time which gives you plenty of time

to wipe off the excess glaze. Even if the glaze gets a bit too

dry to work, you can easily put a little solvent on the rag and

continue working. The glaze requires at least 24 hours to dry

before continuing with the next step.

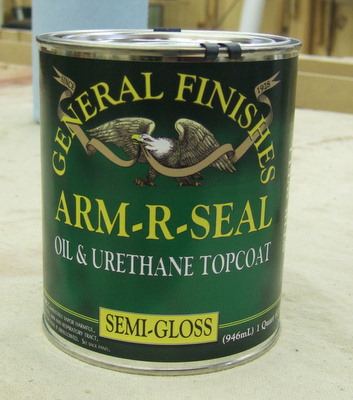

Step 4: Apply the top coats

I

used a water-based wipe on top coat that I applied directly over the

glazed surface. Because the top coat uses a different solvent

than the glaze, I was able to apply it directly over the glaze.

If I had used an oil-based top coat instead, I might have chosen to

seal the glaze first with a thin coat of shellac. I applied the

top coat with a rag following the instructions on the can. I

applied a total of three coats sanding very lightly in between coats.