|

This

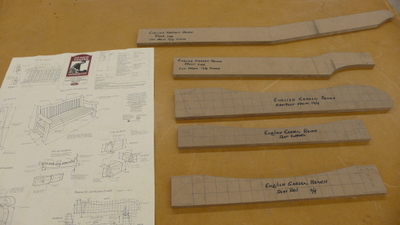

project is all about making templates and I took a lot of time to make

the templates as accurate as possible. The technique I use is

to

use the templates to rough out the shape on the bandsaw and then make

an exact copy on the router table using a pattern bit. This

technique makes it possible to produce as many copies of a particular

piece as I need and they will all be exactly the same. |

|

The

templates also come in very handy to help get as much yield out of an

expensive piece of wood . Here I'm using the templates to

figure

out where each piece will come out of the board. |

|

Here

the two arms have been rough cut. The critical angle on the

left

of each arm had to be precise or else the arms would not have parallel

with the ground when attached to the backs. After this cut

was

made on the table saw I used a bandsaw to rough out the curved cuts

staying well away from the line. |

|

Here

I'm using a pattern bit on my router table to refine the shape exactly

to the template. The 1/2 inch MDF template has been attached

to

the workpiece using double sided tape. The hight of the

router

bit is set so that the bearing rides along the template and the bit

cuts the wood. Because this stock is 12/4 (e.g.: 3 inches

thick)

the bit I'm using can only do half the profile. After this

step

is complete, I used another pattern bit with the bearing on the top,

removed the MDF template, then finished the cut by referencing the

bearing against the part finished in this step. The result is

a

three inch piece cut to the exact shape of the template. |

|

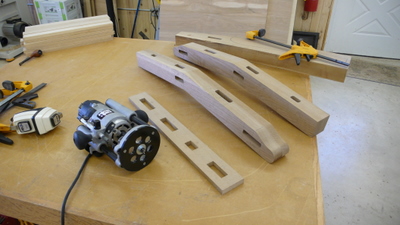

The

mortises needed to be cut an inch and a half deep and were 3/4 inches

wide. There are many ways to cut mortises and for these I

chose

to make another template for the four different mortise lengths I would

be cutting. The size of each hole is adjusted to accomodate

the

guide bushing I've installed on the router and also considers the

diameter of the router bit. The advantage of this technique

was

that I was able to very precisely position the template on the work

piece to locate the mortise as accurate as possible. The

disadvantage is that I ended up with rounded corners that I had to

chisel square so the tenons would fit properly. |

|

Here I'm using the template I describe above to

cut one of the mortises. |

|

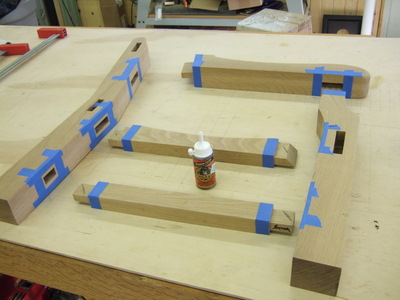

Polyurathane

glue has excellent outdoor properties so it was the natural choice.

It is, however, a very messy glue and it is very difficult to

clean any squeeze out. During the dry fit I clamped the

assembly

together and applied blue tape to the joints. This technique

catches 99% of the glue squeeze out. |

|

After

glueing and clamping, I drilled 3/8 inch holes into and through each

tenon, applied some glue, then drove in 3/8 inch birch dowels.

This is called "pegging the tenon" and this technique has

been

used for hundreds of years to added incredible strength to a mortise

and tenon joint. After the pegs were inserted, the clamps

were no

longer needed. |

|

Here I've setup my hollow chisel mortise machine

to cut the angled mortises for the slats along the bottom back rail.

|

|

Here

I've setup to cut the cheeks on the tenons on one of the back members.

I needed every bit of my 10 foot ceiling height to pull this

off. |

|

At the dry fit stage before glue I'm laying out

exactly where I want the pegs to go to peg the tenons. |

|

The woodworking is complete and its time to enjoy

a cup and reflect on a really fun project! |